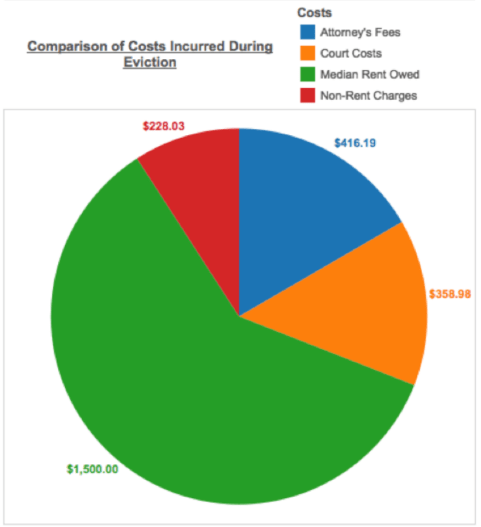

A new report from the Seattle Women’s Commission and the Housing Justice Project on who gets evicted in Seattle, and why, concludes that not only are women and people of color more likely to get evicted than white men, but that they often lose their homes over very small amounts of money—just a few hundred dollars in late rent, which is usually compounded by the addition of court and attorney’s fees. Among all the people evicted for failure to pay rent on time, more than half (52.3 percent) owed one month’s rent or less, and more than three-quarters (76.6 percent) owed less than $2,500 ($1,236 on average.) Because evicted tenants are generally required to pay additional court costs, attorneys’ fees, and other non-rent charges on top of the rent they owe, the median court judgment was $3,129.

Sarah Stewart, a longtime Seattle resident who has been living in her car since she was evicted this past March, said at a press conference today that she lost her apartment, in a low-income building, because her landlord miscalculated her income, which varies from month to month based on her ability to work. Stewart has a degenerative illness that causes pain and fatigue. Despite her family’s efforts to help her pay “the enormous amounts they demanded,” she eventually ended up in eviction court. “In the end,” she said, “the landlord had all the power, and not only were they able to evict me, but they also burdened me with over $2,000 in late fees, attorneys’ fees and non-rent fees. In my current situation, there is no way I will ever be able to pay that back.”

The report, “Losing Home: The Human Cost of Eviction in Seattle,” describes a system heavily weighted in favor of landlords and against tenants, particularly tenants who lack attorneys. The vast majority of people who get evicted (87.5 percent) in Seattle ended up homeless (a category that includes couch surfing or living in shelters in addition to unsheltered homelessness) for the exact reason you might expect: Once you’ve got an eviction on your record, it can be nearly impossible to find someone willing to rent to you.

Eviction prevention programs in Seattle are virtually nonexistent—in sharp contrast to other cities such as New York, where the Bronx Housing Court, which offers a one-stop shop for rental assistance programs, has helped prevent evictions in 86 percent of cases. (Other cities also give tenants sore time to pay what they owe—in Seattle, the eviction process can begin as soon as you’re three days late on your rent—and offer more discretion to judges to work out deals between landlords and tenants that allow people to stay in their homes). This can be traced, in part, to a 2016 report that recommended diverting funds away from eviction prevention and into programs to help people who are already homeless; that report ended up being the basis of the city’s “Pathways Home” strategy for addressing homelessness.

According to the report, “The Focus Strategies report acknowledged that ‘[t]raditional prevention generally targets households who have their own rental unit and have received an eviction notice,’ but then discouraged such an approach without providing any support for their recommendation. The Focus Strategies report claimed that ‘since most people do not become homeless straight from an eviction, it does not make sense to prioritize sheltering that group of people who are facing eviction; however, this overlooks the collateral consequences of eviction such as poor health, family instability, and higher financial strain on the shelter system.

The problem with ignoring people until they get evicted, Housing Justice Project attorney Ed Witter said today, is that it costs far more—between $15,000 and $17,000—to put someone up in a shelter for a year than it does to pay the $100 or $1,200 or $2,000 that separates them from eviction. “We don’t help [people] until they’ve lost their housing, and we know this isn’t the most efficient way,” Witter said. A client who lived in low-income housing had just been evicted over $15.67 in late rent, Witter continued. “How did we get to the point that tenants are losing their housing over 15 dollars and 67 cents?”

Read the whole report, which includes detailed demographic data on who gets evicted and why as well as policy recommendations, here.

Thank you for covering this. It is critical that Seattle, King County, & WA state make changes to the eviction process.

A correction though…I stated that “I simply couldn’t keep paying the erroneous amounts they demanded. My geriatric mother, who has a traumatic brain injury, even drained her savings & tapped into her retirement account to keep me housed, but it still wasn’t enough.”

The “erroneous amounts” ended up compounding over time to a larger sum. While I was able to get some funding from non-profits, it is a long, byzantine process, so my worried Mom insisted she help out despite it’s impact on her as well.

Thank you again, Sarah